Greek Goddesses of Arts and Sciences Greek God Drawings

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, the Muses (Ancient Greek: Μοῦσαι, romanized: Moûsai , Greek: Μούσες, romanized: Múses ) are the inspirational goddesses of literature, scientific discipline, and the arts. They were considered the source of the knowledge embodied in the poetry, lyric songs, and myths that were related orally for centuries in ancient Greek civilization.

In modernistic figurative usage, a Muse may be a source of artistic inspiration.

Etymology [edit]

The word Muses (Ancient Greek: Μοῦσαι, romanized: Moûsai ) perhaps came from the o-course of the Proto-Indo-European root *men- (the basic meaning of which is "put in mind" in verb formations with transitive office and "have in mind" in those with intransitive function),[ii] or from root *men- ("to tower, mountain") since all the nearly important cult-centres of the Muses were on mountains or hills.[iii] R. Southward. P. Beekes rejects the latter etymology and suggests that a Pre-Greek origin is also possible.[four]

Number and names [edit]

The earliest known records of the Muses come from Boeotia (Boeotian muses). Some ancient authorities regarded the Muses as of Thracian origin.[v] In Thrace, a tradition of three original Muses persisted.[6]

In the start century BC, Diodorus Siculus cited Homer and Hesiod to the contrary, observing:

Writers similarly disagree also concerning the number of the Muses; for some say that at that place are three, and others that at that place are nine, but the number nine has prevailed since it rests upon the authority of the most distinguished men, such as Homer and Hesiod and others like them.[seven]

Diodorus states (Book I.xviii) that Osiris first recruited the nine Muses, forth with the satyrs, while passing through Aethiopia, before embarking on a tour of all Asia and Europe, educational activity the arts of tillage wherever he went.

According to Hesiod'due south account (c. 600 BC), generally followed by the writers of antiquity, the 9 Muses were the nine daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (i.e., "Retention" personified), figuring every bit personifications of knowledge and the arts, specially poetry, literature, trip the light fantastic and music.

The Roman scholar Varro (116–27 BC) relates that there are only three Muses: one born from the movement of water, another who makes sound by striking the air, and a third who is embodied only in the human voice. They were called Melete or "Do", Mneme or "Memory" and Aoide or "Vocal". The Quaestiones Convivales of Plutarch (46–120 AD) as well report three ancient Muses (9.I4.2–four).[8] [9]

However, the classical understanding of the Muses tripled their triad and established a set of nine goddesses, who embody the arts and inspire creation with their graces through remembered and improvised song and mime, writing, traditional music, and dance. It was non until Hellenistic times that the post-obit systematic set of functions became associated with them, and even and then some variation persisted both in their names and in their attributes:

Mosaic with symbols of each Muse and Mnemosyne, 1st century BC, Archaeological Museum of Ancient Elis.

- Calliope (ballsy poesy)

- Clio (history)

- Euterpe (flutes and music)

- Thalia (comedy and pastoral poetry)

- Melpomene (tragedy)

- Terpsichore (trip the light fantastic toe)

- Erato (love poesy and lyric poetry)

- Polyhymnia (sacred poetry)

- Urania (astronomy)

According to Pausanias, who wrote in the later 2nd century Ad, at that place were originally 3 Muses, worshipped on Mount Helicon in Boeotia: Aoide ("song" or "tune"), Melete ("practice" or "occasion"), and Mneme ("memory").[10] Together, these three form the complete picture of the preconditions of poetic art in cult practice.

In Delphi too three Muses were worshiped, but with other names: Nete, Mese, and Hypate, which are assigned every bit the names of the three chords of the ancient musical instrument, the lyre.[11]

Alternatively, after they were called Cephisso, Apollonis, and Borysthenis - names which characterize them as daughters of Apollo.[12]

A later tradition recognized a ready of four Muses: Thelxinoë, Aoide, Archē, and Melete, said to be daughters of Zeus and Plusia or of Ouranos.[xiii]

One of the people frequently associated with the Muses was Pierus. Past some he was chosen the father (by a Pimpleian nymph, called Antiope by Cicero) of a total of 7 Muses, chosen Neilṓ (Νειλώ), Tritṓnē (Τριτώνη), Asōpṓ (Ἀσωπώ), Heptápora (Ἑπτάπορα), Achelōís, Tipoplṓ (Τιποπλώ), and Rhodía (Ῥοδία).[14] [15]

Mythology [edit]

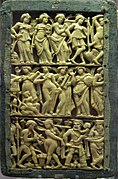

Thalia, Muse of one-act, holding a comic mask (item from the "Muses Sarcophagus")

Co-ordinate to Hesiod's Theogony (seventh century BC), they were daughters of Zeus, rex of the gods, and Mnemosyne, Titan goddess of memory. Hesiod in Theogony narrates that the Muses brought to people forgetfulness, that is, the forgetfulness of pain and the abeyance of obligations.[sixteen]

For Alcman and Mimnermus, they were even more primordial, springing from the early deities Ouranos and Gaia. Gaia is Mother Earth, an early on mother goddess who was worshipped at Delphi from prehistoric times, long earlier the site was rededicated to Apollo, perhaps indicating a transfer to association with him after that time.

Sometimes the Muses are referred to as h2o nymphs, associated with the springs of Helicon and with Pieris. It was said that the winged horse Pegasus touched his hooves to the basis on Helicon, causing four sacred springs to burst forth, from which the Muses, likewise known as pegasides, were born.[17] [18] Athena afterwards tamed the horse and presented him to the Muses (compare the Roman inspiring nymphs of springs, the Camenae, the Völva of Norse Mythology and also the apsaras in the mythology of classical India).

Classical writers set Apollo equally their leader, Apollon Mousēgetēs ("Apollo Muse-leader").[nineteen] In one myth, the Muses judged a contest between Apollo and Marsyas. They also gathered the pieces of the dead body of Orpheus, son of Calliope, and buried them in Leivithra. In a later myth, Thamyris challenged them to a singing contest. They won and punished Thamyris by blinding him and robbing him of his singing power.

According to a myth from Ovid'due south Metamorphoses—alluding to the connection of Pieria with the Muses—Pierus, king of Macedon, had ix daughters he named after the nine Muses, assertive that their skills were a dandy match to the Muses. He thus challenged the Muses to a match, resulting in his daughters, the Pierides, beingness turned into chattering jays (with κίσσα often erroneously translated as magpies) for their presumption.[20]

Pausanias records a tradition of ii generations of Muses; the first are the daughters of Ouranos and Gaia, the 2nd of Zeus and Mnemosyne. Another, rarer genealogy is that they are daughters of Harmonia (the daughter of Aphrodite and Ares), which contradicts the myth in which they were dancing at the wedding of Harmonia and Cadmus.

Children [edit]

Calliope had Ialemus and Orpheus with Apollo. Just according to a variation, the father of Orpheus was actually Oeagrus, only Apollo adopted the male child and taught him the skill of lyre. Calliope trained him in singing.

Linus was said[21] to have been the son of Apollo and 1 of the Muses, either Calliope or Terpsichore or Urania. Rhesus was the son of Strymon and Calliope or Euterpe.

The sirens were the children of Achelous and Melpomene or Terpsichore. Kleopheme was the daughter of Erato and Malos. Hyacinth was the son of Clio, co-ordinate to an unpopular business relationship.

Hymenaeus was assigned as Apollo'south son by one of the muses, either Calliope, or Clio, or Terpsichore, or Urania. Corybantes were the children of Thalia and Apollo.

Cult [edit]

The Muses had several temples and shrines in ancient Greece, their two chief cult centres being Mount Helikon in Boiotia and Pieria in Makedonia. Strabo wrote:

- "Helikon, non far distant from Parnassos, rivals it both in height and in excursion; for both are rocky and covered with snow, and their excursion comprises no large extent of territory. Here are the temple of the Mousai and Hippukrene and the cavern of the Nymphai called the Leibethrides; and from this fact i might infer that those who consecrated Helikon to the Mousai were Thrakians, the aforementioned who dedicated Pieris and Leibethron and Pimpleia [in Pieria] to the aforementioned goddesses. The Thrakians used to be chosen Pieres, merely, at present that they take disappeared, the Makedonians hold these places."[22]

The cult of the Muses was too commonly connected to that of Apollo.

Emblems [edit]

| Muse | Domain | Keepsake |

|---|---|---|

| Calliope | Epic poetry | Writing tablet, Stylus, Lyre |

| Clio | History | Scrolls, Books, Cornett, Laurel wreath |

| Erato | Love poetry | Cithara (an ancient Greek musical instrument in the lyre family) |

| Euterpe | Music, Song, and Lyric poetry | Aulos (an ancient Greek musical musical instrument like a flute), panpipes, laurel wreath |

| Melpomene | Tragedy | Tragic mask, Sword (or any kind of blade), Club, Kothornos (boots) |

| Polyhymnia | Hymns | Veil, Grapes (referring to her as an agricultural goddess) |

| Terpsichore | Dance | Lyre, Plectrum |

| Thalia | Comedy | Comic mask, Shepherd's crook (the vaudeville act of pulling someone off the stage with a claw is a reference to Thalia'due south crook), Ivy wreath |

| Urania | Astronomy (Christian verse in later times) | Globe and compass |

Some Greek writers give the names of the nine Muses as Kallichore, Helike, Eunike, Thelxinoë, Terpsichore, Euterpe, Eukelade, Dia, and Enope.[23]

In Renaissance and Neoclassical art, the dissemination of emblem books such as Cesare Ripa'southward Iconologia (1593 and many further editions) helped standardize the delineation of the Muses in sculpture and painting, so they could be distinguished by certain props. These props, or emblems, became readily identifiable by the viewer, enabling i immediately to recognize the Muse and the art with which she had become associated. Hither once more, Calliope (ballsy poetry) carries a writing tablet; Clio (history) carries a scroll and books; Euterpe (song and elegiac verse) carries a flute, the aulos; Erato (lyric poesy) is oftentimes seen with a lyre and a crown of roses; Melpomene (tragedy) is often seen with a tragic mask; Polyhymnia (sacred poetry) is oftentimes seen with a pensive expression; Terpsichore (choral trip the light fantastic toe and vocal) is ofttimes seen dancing and carrying a lyre; Thalia (comedy) is often seen with a comic mask; and Urania (astronomy) carries a pair of compasses and the celestial world.

Functions [edit]

In gild [edit]

The Greek give-and-take mousa is a common noun besides as a type of goddess: it literally ways "art" or "poetry". Co-ordinate to Pindar, to "carry a mousa" is "to excel in the arts". The give-and-take derives from the Indo-European root men-, which is besides the source of Greek Mnemosyne and mania, English language "mind", "mental" and "monitor", Sanskrit mantra and Avestan Mazda.[24]

The Muses, therefore, were both the embodiments and sponsors of performed metrical speech communication: mousike (whence the English language term "music") was just "1 of the arts of the Muses". Others included Scientific discipline, Geography, Mathematics, Philosophy, and especially Fine art, Drama, and inspiration. In the archaic period, before the widespread availability of books (scrolls), this included most all of learning. The first Greek book on astronomy, past Thales, took the form of dactylic hexameters, equally did many works of pre-Socratic philosophy. Both Plato and the Pythagoreans explicitly included philosophy equally a sub-species of mousike.[25] The Histories of Herodotus, whose primary medium of commitment was public recitation, were divided by Alexandrian editors into nine books, named subsequently the nine Muses.

For poet and "law-giver" Solon,[26] the Muses were "the primal to the good life"; since they brought both prosperity and friendship. Solon sought to perpetuate his political reforms by establishing recitations of his poetry—complete with invocations to his applied-minded Muses—by Athenian boys at festivals each yr. He believed that the Muses would aid inspire people to do their best.

In literature [edit]

Ancient authors and their imitators invoke Muses when writing poetry, hymns or epic history. The invocation occurs virtually the beginning of their work. Information technology asks for aid or inspiration from the Muses, or but invites the Muse to sing directly through the author.

Originally, the invocation of the Muse was an indication that the speaker was working inside the poetic tradition, according to the established formulas. For instance:

These things declare to me from the starting time,

ye Muses who dwell in the business firm of Olympus,

and tell me which of them first came to be.

— Hesiod (c. 700 BCE), Theogony (Hugh K. Evelyn-White translation, 2015)

Sing to me of the human being, Muse, the man of twists and turnsdriven time and once again off course, once he had plundered

the hallowed heights of Troy.

- —Homer (c. 700 - 600 BCE), in Book I of The Odyssey (Robert Fagles translation, 1996)

O Muse! the causes and the crimes chronicle;

What goddess was provok'd, and whence her hate;

For what offense the Queen of Heav'n began

To persecute so dauntless, so but a man; [...]

- —Virgil (c. 29 - 19 BCE), in Book I of the Aeneid (John Dryden translation, 1697)

Besides Homer and Virgil, other famous works that included an invocation of the Muse are the outset of the carmina by Catullus, Ovid's Metamorphoses and Amores, Dante's Inferno (Canto Ii), Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde (Volume Two), Shakespeare's Henry V (Act i, Prologue), his 38th sonnet, and Milton's Paradise Lost (openings of Books i and seven).

In cults and modernistic museums [edit]

When Pythagoras arrived at Croton, his first advice to the Crotoniates was to build a shrine to the Muses at the eye of the city, to promote civic harmony and learning. Local cults of the Muses frequently became associated with springs or with fountains. The Muses themselves were sometimes called Aganippids because of their association with a fountain called Aganippe. Other fountains, Hippocrene and Pirene, were also of import locations associated with the Muses. Some sources occasionally referred to the Muses as "Corycides" (or "Corycian nymphs") after a cavern on Mount Parnassos, called the Corycian Cavern. Pausanias referred to the Muses by the surnames "Ardalides" or "Ardaliotides", because of a sanctuary to them at Troezen said to have been congenital by the mythical Ardalus.

The Muses were venerated particularly in Boeotia, in the Valley of the Muses near Helicon, and in Delphi and the Parnassus, where Apollo became known as Mousēgetēs ("Muse-leader") afterward the sites were rededicated to his cult.

Frequently Muse-worship was associated with the hero-cults of poets: the tombs of Archilochus on Thasos and of Hesiod and Thamyris in Boeotia all played host to festivals in which poetic recitations accompanied sacrifices to the Muses. The Library of Alexandria and its circle of scholars formed effectually a mousaion (i.e., "museum" or shrine of the Muses) close to the tomb of Alexander the Great. Many Enlightenment figures sought to re-establish a "Cult of the Muses" in the 18th century. A famous Masonic gild in pre-Revolutionary Paris was called Les Neuf Soeurs ("The Nine Sisters", that is, the 9 Muses); Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin, Danton, and other influential Enlightenment figures attended it. As a side-event of this movement the word "museum" (originally, "cult place of the Muses") came to refer to a place for the public brandish of knowledge.

Places named after the Muses [edit]

In New Orleans, Louisiana, there are streets named for all nine. It is commonly held that the local pronunciation of the names has been colorfully anglicized in an unusual way by the "Yat" dialect. The pronunciations are actually in line with the French, Spanish and Creole roots of the city.[27]

Modernistic employ in the arts [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. You tin help past adding to it. (January 2022) |

The Muses are explicitly used in modern English to refer to an artistic inspiration,[28] as when 1 cites one's own artistic muse, and also implicit in words and phrases such equally "amuse", "museum" (Latinised from mouseion—a place where the Muses were worshipped), "music", and "musing upon".[29] In current literature, the influential role that the Muse plays has been extended to the political sphere.[xxx]

Gallery [edit]

See also [edit]

- Apsara

- Artistic inspiration

- Divine inspiration

- Leibethra

- Pimpleia

- Saraswati

- Muses in popular culture

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Clio". lib.ugent.be . Retrieved 2020-09-28 .

- ^ Westward 2007, p. 34.

- ^ * A. B. Cook (1914), Zeus: A Study in Aboriginal Religion, Vol. I, p. 104, Cambridge Academy Press.

- ^ R. Due south. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 972.

- ^ H. Munro Chadwick, Nora K. Chadwick (2010). The Growth of Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9781108016155.

- ^ At to the lowest degree, this was reported to Pausanias in the second century AD. Cfr. Karl Kerényi: The Gods of the Greeks, Thames & Hudson, London 1951, p. 104 and note 284.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 4.7.i–ii (on-line text)

- ^ See also the Italian article on this writer.

- ^ Susan Scheinberg, in reporting other Hellenic maiden triads in "The Bee Maidens of the Homeric Hymn to Hermes", references Diodorus, Plutarch and Pausanias - Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 83 (1979:1–28), p. 2.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Hellenic republic ix.29.ane–9.29.2

- ^ Plutarch Symposium 9.fourteen

- ^ Eumelus fr. 35 as cited from Tzetzes on Hesiod, 23; Tzetzes on Hesiod, Works and Days six

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.53, Epicharmis, Tzetzes on Hes. 23

- ^ Epicharmis, Tzetzes on Hes. 23

- ^ Smith, William; Lexicon of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Musae" .

- ^ Commonage piece of work by scholars and expertise (1980). Επιστήμη & Ζωή (Printed ed.). Greece: CHATZIAKOVOU Southward.A. pp. Vol.13, p.151.

- ^ "Elysium Gates - Historical Pegasus". Archived from the original on 2009-06-16. Retrieved 2010-02-26 .

- ^ Ovid, Heroides 15.27: "the daughters of Pegasus" in the English translation; Propertius, Poems 3.1.nineteen: "Pegasid Muses" in the English translation.

- ^ For instance, Plato, Laws 653d.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.677–78: "Now their previous eloquence likewise remained in the birds, too every bit their strident chattering and their great zeal for speaking." See also Antoninus Liberalis ix.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca 1.3.2

- ^ Strabo, Geography ix. 2. 25 (trans. Jones)

- ^ Tzetzes, Scholia in Hesiodi Opera 1,23

- ^ Calvert Watkins, ed., The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, 3d ed., p. 56.

- ^ Strabo ten.3.x.

- ^ Solon, fragment thirteen.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: NOLA.com. "How to pronounce New Orleans Muses Streets" – via YouTube.

- ^ "muse". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford Academy Press. (Subscription or participating establishment membership required.) Mainly 1b, 2

- ^ OED derives "amuse" from French a- ("from") and muser, "to stare stupidly or distractedly".

- ^ Sorkin, Adam J. (1989) Politics and the Muse. Studies in the Politics of Recent American Literature. Bowling Green State Academy Popular Printing, Bowling Green OH.

References [edit]

- Due west, Martin Fifty. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-19-928075-9.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. nineteen (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–60.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muses. |

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Muses |

- Muses in ancient fine art; ancientrome.ru

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (c. 1,000 images of the Muses)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muses

0 Response to "Greek Goddesses of Arts and Sciences Greek God Drawings"

Post a Comment